Exploration of the Bird of Paradise

Table of Contents

The Origin of the Apus Constellation

Our night sky is filled with countless formations, each with its own unique story, scientific history, and astronomical significance. Among these is Apus, a small but fascinating constellation located in the southern celestial hemisphere. Representing the exotic bird of paradise, Apus has a rich history that is linked to famous the Age of Exploration and gives us a unique glimpse into the lesser-known stars and deep-sky objects of our night sky. In this article, we will take a deep look the origins of the Apus constellation, its historical and cultural significance, its stars, and the notable celestial objects it contains.

Etymology and Early History

The name “Apus” is derived from the Greek word “apous,” meaning “footless.” This unusual name comes from a historical misconception: early European explorers who encountered birds of paradise in newly explored land believed these birds lacked feet because the specimens they saw were often prepared without them. These exotic birds, with their colourful plumage caught the attention of people in the Renaissance period, leading to the constellation’s name.

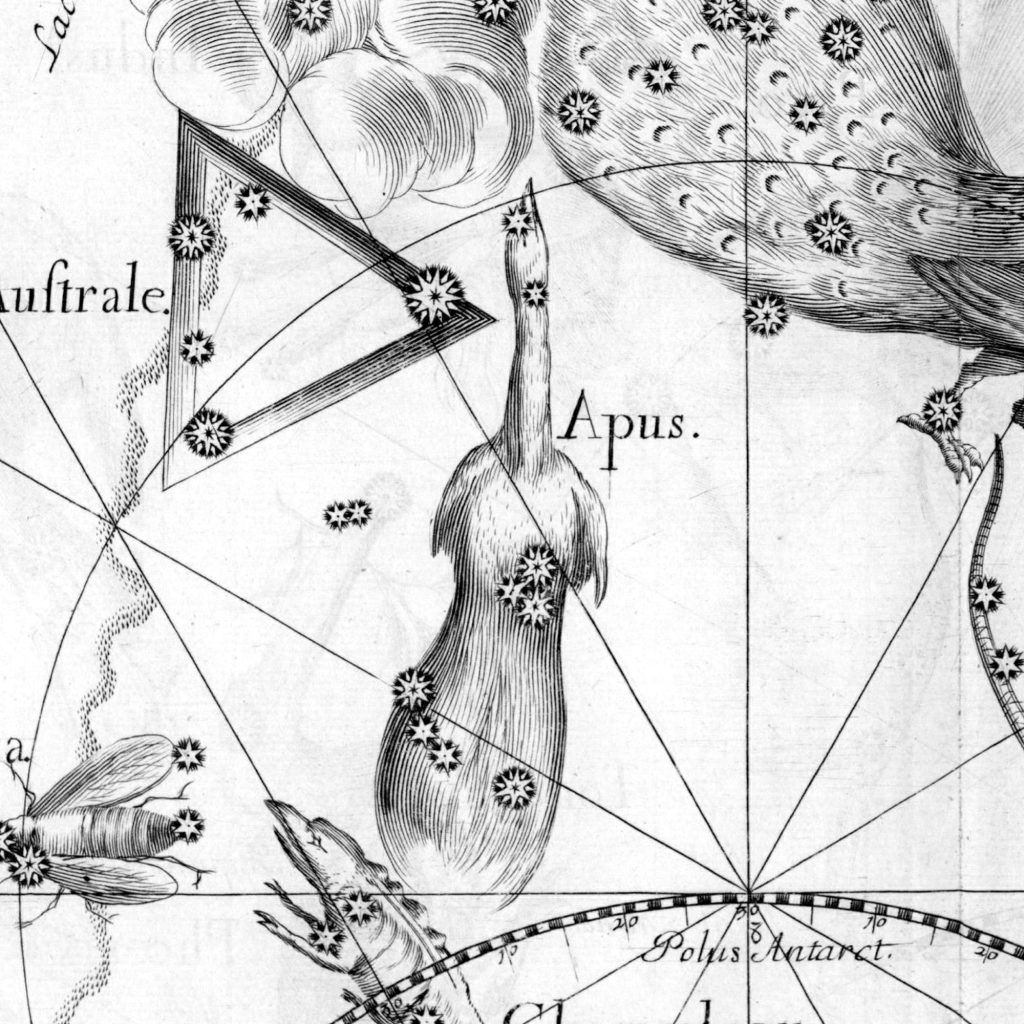

The constellation Apus was created by the Dutch-Flemish astronomer and cartographer Petrus Plancius in the late 16th century. Plancius was a key figure in the Age of Exploration, utilizing the observations made by Dutch navigators Pieter Dirkszoon Keyser and Frederick de Houtman. These navigators charted the southern skies during their voyages, contributing significantly to the star maps of that time. Apus was first catalogued by Plancius in 1598 and later included in Johann Bayer’s 1603-star atlas, Uranometria, where it gained broader recognition.

The constellation name Apus is pronounced /ˈeɪpəs/. In English, it is known as the Bird-of-Paradise. The genitive form of Apus, used in star names, is Apodis (pronunciation: /ˈæpoʊdɪs/). The three-letter abbreviation, adopted by the International Astronomical Union (IAU) in 1922, is Aps.

Historical Naming Confusions

Initially, Plancius named the constellation “Paradysvogel Apis Indica” which translates to “Indian bird of paradise.” However, this name caused some confusion due to the use of “Apis”, the Latin word for bee. This error was later corrected, but not before the name Apis had caused some mix-ups. The constellation was alternatively referred to as “Avis Indica”, with Avis meaning bird in Latin. Over time, the name evolved and settled as Apus, while the term Apis was reassigned to represent the constellation Musca, the fly.

In 1763, the French astronomer Nicolas Louis de Lacaille officially used the name Apus in his chart of the southern skies. Despite the initial confusion, the name Apus has stuck with us, and the constellation remains a tribute to the colourful birds in the Age of Exploration.

Lack of Mythological Context

Unlike many constellations in the northern hemisphere that have their roots in ancient mythology from civilizations like Greece and Rome, Apus does not have a rich mythological background. This absence of mythological tales can be credited to its relatively recent introduction to star maps during the Renaissance, a time when European explorers were charting the unknown southern skies rather than drawing from ancient myths.

Location and Visibility

Geographical Placement and Observation

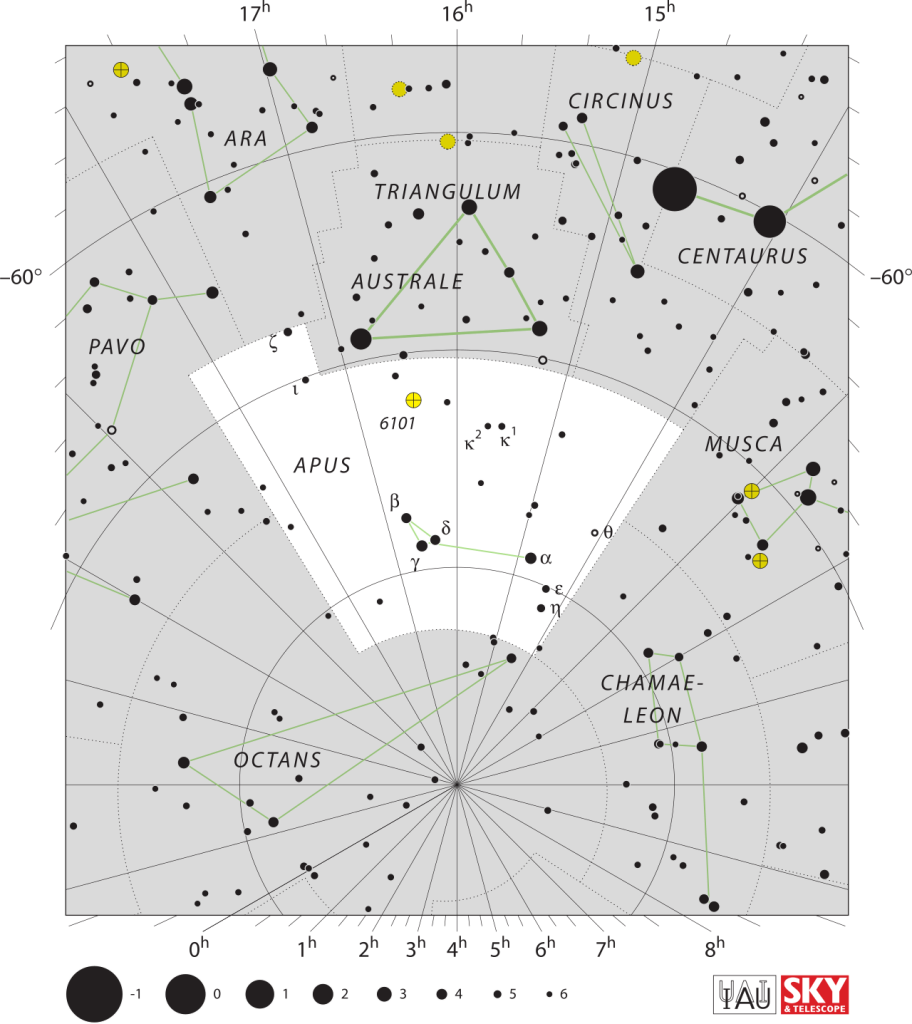

Apus is the 67th largest constellation in the sky, occupying an area of ~206 square degrees. It is situated in the third quadrant of the southern hemisphere and is bordered by several other constellations: Ara to the northwest, Chamaeleon to the east, Circinus to the north, Musca to the southwest, Octans to the south, Pavo to the west, and Triangulum Australe to the northeast. Its position makes it primarily visible from the southern hemisphere, with latitudes ranging from +5° to -90° (roughly from the Equator to the South Pole).

For observers in the southern hemisphere, Apus is a circumpolar constellation, meaning it is visible throughout the year, and it never sets. The constellation is not visible in the Northern Hemisphere, since it is far below the horizon.

Mapping Apus

To locate Apus in the night sky, it is helpful to identify its neighbouring constellations first. For instance, the bright stars of Triangulum Australe and the distinctive shape of Pavo can serve as reference points. Once you identify these constellations, you can spot Apus among them, a subtle presence in the southern celestial hemisphere.

The Stars of Apus

Apus is not known for having exceptional celestial objects, but it does feature several noteworthy ones, each contributing to the constellation’s unique character. Here is a closer look at some of the primary stars in Apus:

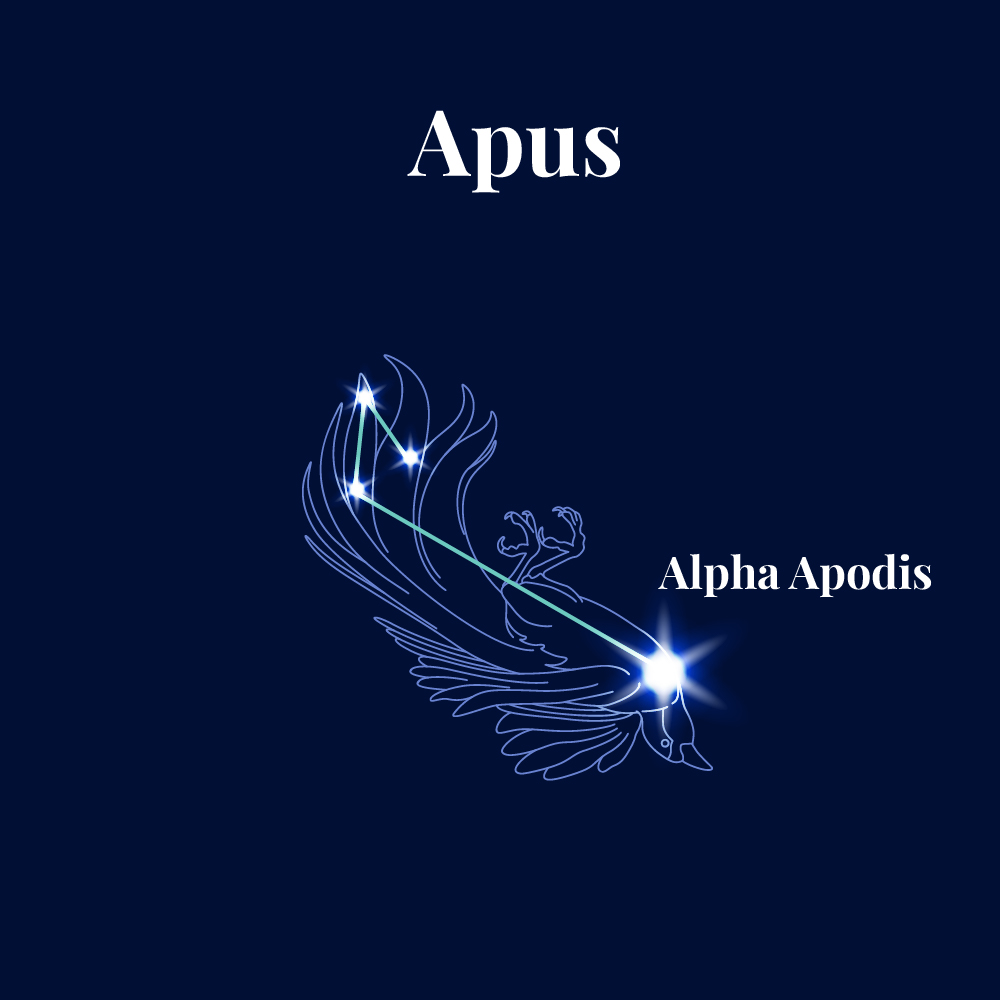

Alpha Apodis (α Apodis)

This is the brightest star in the constellation. Alpha Apodis is a K-type giant with an apparent magnitude of 3.825. The K-type means that the star had already consumed its hydrogen “fuel” and evolved from its main sequence. It is certainly not our neighbour: it is approximately 410 light-years away from Earth. Alpha Apodis is an orange giant star, indicating it is in the later stages of its stellar evolution – according to scientists, it’s photosphere has an effective temperature of 4,090 K (3,816 degrees Celsius).

Gamma Apodis (γ Apodis)

Gamma Apodis is the second brightest star in Apus, with an apparent magnitude of 3.872. This yellow G-type giant star is about 160 light-years from Earth. Gamma Apodis represents the typical characteristics of a giant star, having exhausted the hydrogen in its core and expanded significantly.

Delta Apodis (δ Apodis)

Delta Apodis is a binary star system, approximately 800 light-years distant. The primary star, Delta-1 Apodis, is an M-type red giant with irregular variability in its brightness, fluctuating between magnitudes 4.66 and 4.87. The secondary star, Delta-2 Apodis, is an orange K-type giant with an apparent magnitude of 5.27, located 102.9 arcseconds away from Delta-1.

Beta Apodis (β Apodis)

Beta Apodis is an orange K-type giant star with an apparent magnitude of 4.23, situated about 158 light-years from Earth. It is the third brightest star in Apus, contributing to the constellation’s subtle glow in the night sky.

Zeta Apodis (ζ Apodis)

Another orange K-type giant, Zeta Apodis has an apparent magnitude of 4.76 and is approximately 312 light-years away. Its characteristics are like those of other K-type giants, with a cooler temperature and expanded outer layers.

Eta Apodis (η Apodis)

Eta Apodis is classified as an Am star, or metallic-line star. This A-type star exhibits peculiar chemical properties, with strong absorption lines of some metals and deficiencies of others. Eta Apodis also emits excess infrared radiation, possibly due to a debris disk orbiting the star at about 31 astronomical units (AU), which equals to 4.6 billion kilometres, or 2.8 billion miles.

Epsilon Apodis (ε Apodis)

Epsilon Apodis is a blue-white B-type main sequence star, approximately 551 light-years from Earth. It is a Gamma Cassiopeiae type variable star, with a mean apparent magnitude of 5.06. Its brightness varies slightly by 0.05 magnitudes due to the outflow of matter from its fast-rotating surface.

Kappa Apodis (κ Apodis)

Kappa Apodis is a designation for two star systems, Kappa-1 and Kappa-2 Apodis. Kappa-1 is a blue-white B-type subgiant and a Gamma Cassiopeiae type variable star, located around 1020 light-years away. Kappa-2 is a binary system with a blue-white B-type giant and an orange K-type main sequence dwarf, separated by 15 arcseconds.

Exoplanets in Apus

According to the latest measurements, HD 134606 (another star in Apus) has its own exoplanet companions.

The discovery of a planetary system around HD 134606 was announced in 2011 after an eight-year survey at the La Silla Observatory in Chile, using the HARPS instrument and the radial velocity method. This data suggested three planets with moderately eccentric orbits, none of which are in mean motion resonance with each other.

A 2024 study updated this system, confirming the three previously reported planets, noting a longer period for planet D, and discovering two new ones. While all five planets are likely real, the study advises caution about planet F due to its period being similar to the lunar cycle. The planets range in mass from super-Earth to super-Neptune. The outermost planet, HD 134606 D, is a small gas giant in the habitable zone and may be a candidate for future space-based direct imaging missions. Additionally, a long-period radial velocity trend suggests a distant sixth substellar companion.

Deep Sky Objects in the Apus constellation

Beyond its stars, Apus hosts several notable deep-sky objects, including globular clusters and galaxies. These objects offer a glimpse into the distant and ancient parts of the universe.

NGC 6101

NGC 6101 is a small globular cluster located seven degrees north of Gamma Apodis. With an apparent magnitude of 9.2, it can be observed through a 4.5-inch telescope. Globular clusters like NGC 6101 are spherical collections of ancient stars bound together by gravity, often found in the halos of galaxies.

IC 4499

IC 4499 is another globular cluster in Apus, known for being the southernmost globular cluster in the sky. This makes it an interesting target for astronomers studying the southern celestial hemisphere.

With an apparent magnitude that requires an at least an eight-inch (~20 cm) telescope to observe, IC 4499 appears as a faint, small patch of light. It lies at the threshold between low-mass globular clusters, which typically form a single generation of stars, and more massive globular clusters, which often have multiple generations of stars. This unique position makes IC 4499 an important object for studying the formation and evolution of globular clusters. Recent observations suggest that IC 4499 is approximately 12 billion years old, aligning it in age with other Milky Way globular clusters.

Galaxies

IC 4633 and IC 4635

These are the brightest galaxies observable in the Apus constellation. Although faint, they can be seen with suitable telescopes. Observing these galaxies allows astronomers to peer into the vast distances beyond our Milky Way, studying the structure and composition of other galactic systems.

NGC 6392

Another galaxy within Apus, NGC 6392 adds to the constellation’s collection of deep sky objects. These galaxies, though not as prominent as those in larger constellations, provide valuable data for astronomers studying the universe’s structure and evolution.

Astronomical Significance and Observations

The stars and deep sky objects in Apus, though not as bright or well-known as those in other constellations, offer a rich field for astronomical observation and study. The constellation’s position in the southern sky makes it an important part of the celestial maps used by astronomers in the southern hemisphere. Observing Apus requires a clear, dark sky, and even smaller binoculars can enhance the viewing experience.

Observing Apus

When to observe

The best time to observe Apus is during the southern hemisphere’s winter months, from June to September, when the constellation is highest in the sky during the evening hours.

Where to observe

Due to its southern latitude, a location in the southern hemisphere, away from city lights and with a clear horizon, will provide the best viewing conditions.

How to observe

While some stars in Apus can be seen with the naked eye, binoculars or a small telescope will enhance the viewing experience. A larger telescope is required to observe the globular clusters and faint galaxies within the constellation.

Apus in Modern Astronomy

In modern astronomy, Apus is classified within the Johann Bayer family of constellations, a group that includes Chamaeleon, Dorado, Grus, Hydrus, Indus, Musca, Pavo, Phoenix, Tucana, and Volans.

Exoplanetary Research

The presence of exoplanets in Apus star systems, such as HD 131664 and HD 134606, underlines the constellation’s importance in the ongoing search for planets beyond our solar system. These exoplanets could give scientists potential insights into the inner working of planetary systems and contribute to our understanding of the conditions that might support life in the habitable zone of stars.

Apus, though a small and relatively obscure constellation, holds an important position in the Southern night sky. Its origins during the Age of Exploration, its connection to the exotic bird of paradise, and its collection of intriguing stars with exoplanets and deep-sky objects make it a fascinating subject for both amateur stargazers and professional astronomers.